Family empowerment of families raising critically ill children at home

Severely disabled children are children with severe physical disabilities and intellectual disabilities, and about 70% of the approximately 36,000 severely disabled children in Japan live with their families in the community1). The number of children with severe physical and mental disabilities who live at home has been increasing in recent years due to the development of medical technology and the trend of society to promote home medical care 2). Based on the Comprehensive Support Law for Persons with Disabilities, which came into effect in April 2013, various efforts have been made in each region as disability welfare services and community life support projects to support the care of children with severe disabilities at home3-5). Care for critically ill children at home covers a wide range from daily life care to medical care, and specialists in various fields such as welfare, medical care, education, and the community demonstrate their respective specialties, it is important to support families of severely ill children at home through multidisciplinary collaboration6-8). According to a previous study that examined recent research trends, it has been reported that the establishment of a support system has led to a situation in which caregivers can positively work on the care of critically ill children at home9). It is thought that the development of the support system had a great impact on the nursing life of families with severely ill children at home.

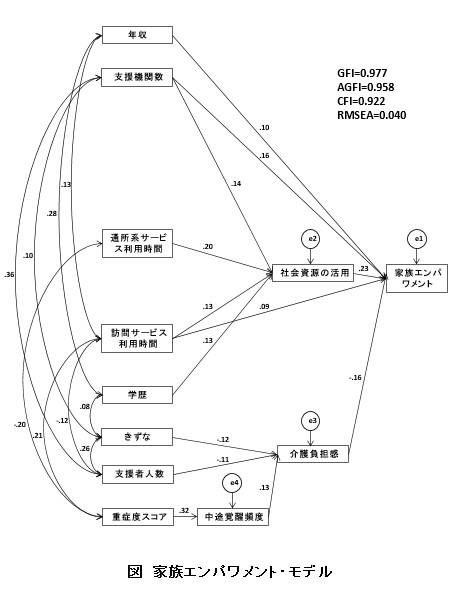

A few years ago, we collected bearer self-administered questionnaires from 1,659 families nationwide with the aim of building an empirical model for family empowerment of children with severe physical and mental disabilities at home. An empirical model was identified by covariance structure analysis (Fig. 1). Family empowerment is defined by “utilization of social resources”, “feeling of burden of long-term care for the main caregiver”, “time to use visiting services”, “number of support organizations”, and “annual income”. “Utilization of social resources” involved “number of support organizations”, “visit service usage time”, “outpatient service usage time”, and “educational background of the main caregiver”. “Frequency of mid-career awakening”, “number of supporters” and “bonds in the family” were involved in the “long-term care burden”. In other words, it became clear that family empowerment is high when the annual income is high, there are many support organizations, social resources are used, the time spent using the visiting service is long, and the burden of long-term care is low.If there were many support organizations, the time spent using outpatient services and visiting services was long, and the educational background was high, social resources could be utilized. On the other hand, when the severity score is high, the frequency of midnight awakening increases and the feeling of burden of long-term care increases. When family ties were strong and there were many supporters, the burden of long-term care was reduced. We will make use of these research findings to raise awareness of the family members or the professional occupations we support.

1) Okada K. History of the Child with Severe Motor and Intellectual Disabilities.The Japanese journal of child nursing, monthly 24:1082-9. 2001(In Japanese).

2) Egusa Y. Habilitation manual for persons with SMID – severe motor and intellectual disabilities. Tokyo: Ishiyaku Publishers, 2005 (In Japanese).

3) Koushinbo H. Partial Revision of the Child Welfare Act, etc. and Future Measures of Persons with Severe Motor and Intellectual Disabilities. Japanese journal of National Medical Services66:498-502. 2012(In Japanese).

4) Takasaki M, Ozawa H, Amemiya K, Nakamura T. Current situations and issues of consultation support specialists in Hachioji city: questionnaire survey results. The Journal of Severe Motor and Intellectual Disabilities 42:399-404. 2017(In Japanese).

5) Hirano E, Takeuchi F, Kashiwagi K. Actual usage of short-term admission for children with severe intellectual and mental disabilities by facility type in Japan. Journal of health and welfare statistics 65: 38-45. 2018 (In Japanese).

6) Tanaka C, Hamabe F, Tawaratsumida Y, Sugawara S. Home support required by people with severe intellectual and mental disabilities in need of medical care and their families. Journal of Severe Motor and Intellectual Disabilities 36: 131-40. 2011 (In Japanese).

7) Takagi S, Okemoto C, Hasegawa T. Needs for the respite service of the primary home caregivers of children or person for severe motor and intellectual disabilities. The Journal of the Nursing Society of University of Toyama 14: 145-58. 2014(In Japanese).

8) Kudo K. Medical, Welfare and education collaborations to ensure home-based play for children with severe physical and mental disabilities: Based on interviews professions who provide support through play. The Bukkyo University Graduate School Review Compiled by the Graduate School of Social Welfare 46: 31-48. 2018(In Japanese).

9) Yokozeki E, Ogawa K. Review of the Literature on the family take care of Technology. Bull. Shikoku Univ. A47:79-86. 2016 (In Japanese).

10) Wakimizu R,Fujioka H,Nishigaki K,Matsuzawa A, Iwata N,Kishino M, Yamaguchi K,Sasaki M. Construction of the empirical model focused on the family empowerment rearing the child with severe motor and intellectual disabilities at home in Japan. The journal of child health, 77(5), pp.423-432. 2018(In Japanese).